Saga Pattern

Implementing transactions that span multiple microservices becomes quite complex, as each microservice has its own private database.

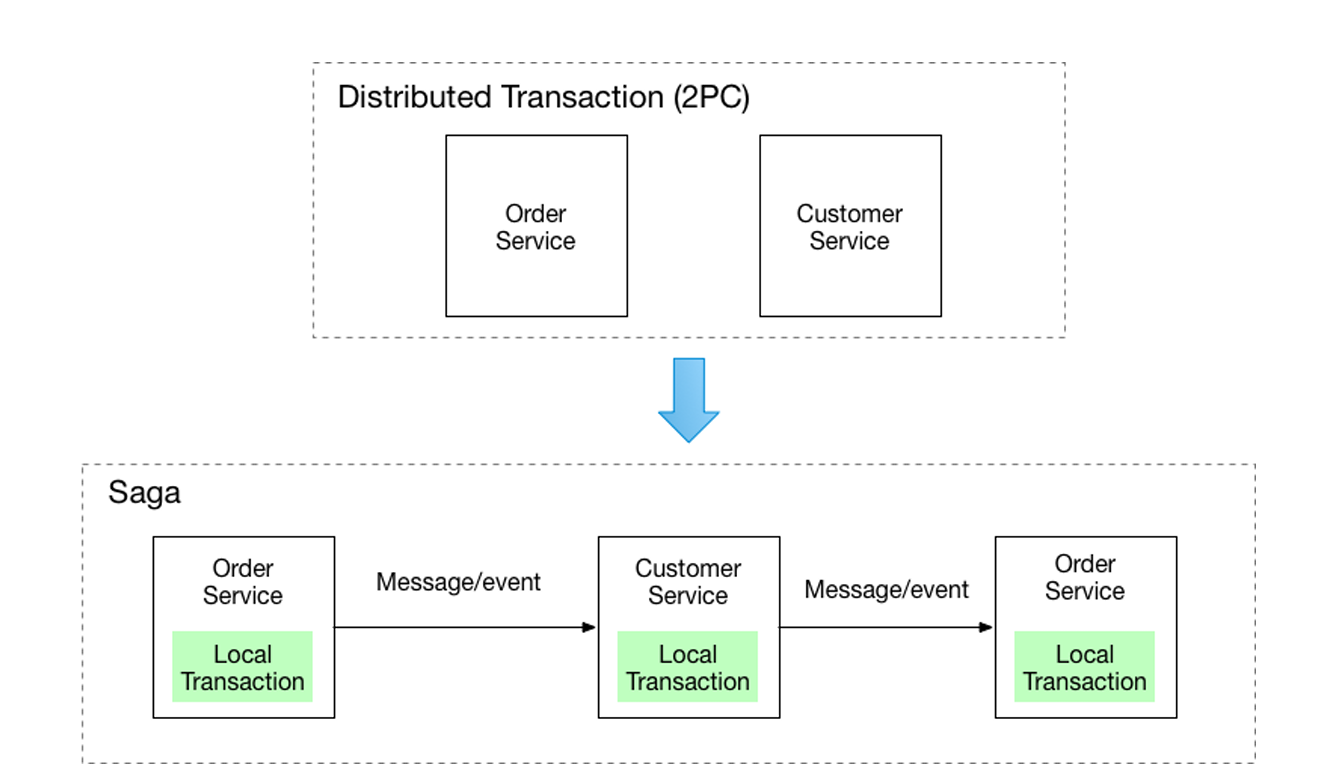

One possible solution is distributed transactions. However, these should not be used in the context of a microservices architecture because they rely on a complex and time-consuming algorithm called 2PC (Two-Phase Commit), which worsens with the increasing number of microservices. Furthermore, distributed transactions are not trivial for ensuring data consistency, use synchronous communications that reduce availability [23, 24]. Additionally, some newer technologies, such as RabbitMQ8 and Apache Kafka9, do not support distributed transactions, limiting their use.

Therefore, to solve the problem, the Saga pattern emerged to maintain data consistency in a microservices architecture without using distributed transactions. A saga is defined for each operation that needs to update multiple microservices, also known as participants.

A saga consists of a sequence of local transactions performed by the involved participants. Each microservice executes a local transaction in its own database and publishes a message or event to trigger the next local transaction in another participant, as shown in Figure 1.

The logic required for implementing the Saga pattern involves selecting and coordinating the participants' steps. Thus, the saga is activated by a system command, implying that the saga coordinator defines and invokes the first participant to execute the local transaction. After this local transaction is completed, the saga coordinator selects and invokes the next participant.

If a participant fails during the execution of the local transaction, the saga coordinator executes a set of compensation transactions to revert the changes made by the preceding microservices. These involve performing an action or functionality contrary to what was executed, as shown in Table 1. This means that if subsequent participants are prone to business failures, it must be ensured that the preceding local transactions have a corresponding compensation transaction.

There are two distinct approaches to coordinating the saga process: choreography and orchestration. The major differences between these approaches lie in the type of coordination and asynchronous communication.

Choreography involves decentralized coordination, where asynchronous communication is event-driven. An event represents a change in the state of a particular object, focused on the event emitter. Each participant in the saga determines the next participant after completing its local transaction, sending an event to it.

In contrast, orchestration involves centralized coordination, where asynchronous communication is message-oriented. A message can be a command or a response. A command message corresponds to a functionality to execute, along with a set of data sent to a destination microservice. A response message contains the data resulting from the execution of an operation. The orchestration approach features centralized coordination by an orchestrator microservice, which determines the next participant and sends command messages with the required data.

The advantage of orchestration is the simplicity of dependencies, with only unidirectional dependencies between the orchestrator and participants. This avoids dependency cycles and simplifies the development of business logic. However, the downside is the centralization of orchestration, which becomes a single point of failure.

In summary, the Saga pattern should be considered in scenarios where performance differences between choreography and orchestration are not a problem. For complex sagas, orchestration is often more suitable.

References

Dissertation: "Study on the importance of the Principles and Patterns of Microservices Architectures", 2023

Website: "Microservice Architecture"